I

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020 threw the worldwide charitable landscape into unprecedented turmoil. Foundations and grantmaking institutions were suddenly subjected to what McKinsey described as “a once-in-a-generation stress test.” This was not only for global health systems, but also for institutional resilience, agility, and purpose-driven project management.

While the charitable sector was able to quickly raise billions of dollars, the crisis revealed significant flaws in old operational methods. Traditional grant cycles, which were rigid, bureaucratic, and risk-averse, were no longer effective in a world demanding instant response. Hence, foundations were forced to reinvent their playbooks as charitable operations ceased, supply chains failed, and community needs increased suddenly. Even more, the pandemic exposed a fundamental truth: resilient grantmaking is dependent not only on funds but also on adaptive project management that balances risk, responsiveness, and results.

While pandemics are considered a “known risk” in long-term planning, philanthropic organizations have often neglected to incorporate this operational uncertainty into their portfolio strategies or Project Management Offices (PMOs). Because of this gap, systems expected to be stable were overtaken by chaos, delaying the help that was required.

This case study leverages professional insights to reveal lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. It also emphasises how grantmaking foundations managed chaos and how the lessons might be applied to the upcoming philanthropic era.

II

The Fundamentals of Agile Project Management in Philanthropy

After the dust settled, foundations discovered a new reality that prioritizes learning, speed, and trust just as much as scale. Agile project management, which is frequently connected to software development, entails substituting creative, collaborative methods that put people, feedback, and flexibility first for inflexible, set procedures. The Agile technique requires grantmakers and nonprofit organizations (NPOs) to prioritize quick change adaptation and to constantly assess the project’s core requirements.

Essentially, Agile’s primary selling point is its capacity to produce adaptable outputs with enhanced social impact at a reduced cost. Significant operational advantages come from using this strategy. They include improved project management, quicker turnaround times, greater adaptability to changing conditions, and decreased waste by using fewer resources. By leveraging the skills of all teams and improving workflow transparency, agile approaches radically change the internal power structure.

Also, agile project management techniques combined with flexible funding transform the grantee from a compliance object into an empowered project manager in the external relationship. Primarily, we can identify several timeless project management lessons in philanthropy going forward:

- Lesson 1: Integrate Agility into Governance: Establish adaptable approval processes and provide teams the freedom to move swiftly within predetermined bounds.

- Lesson 2: Redefine Risk: Transition from risk aversion to risk intelligence by categorizing hazards based on their potential impact rather than their level of anxiety.

- Lesson 3: Collaborate with Grantees to Create: Transition from transactional funding to collaborative design, where communities and grantees influence strategy.

- Lesson 4: Make Data System Investments: Leverage technology to improve learning and transparency, particularly real-time dashboards and APIs.

- Lesson 5: Emphasize Human Resilience: Encourage teams’ mental well-being, flexibility, and ongoing education.

III

Critical Statistics on Agile Project Management

In this section, we will consider critical statistics on the use of Agile Project Management across sectors.

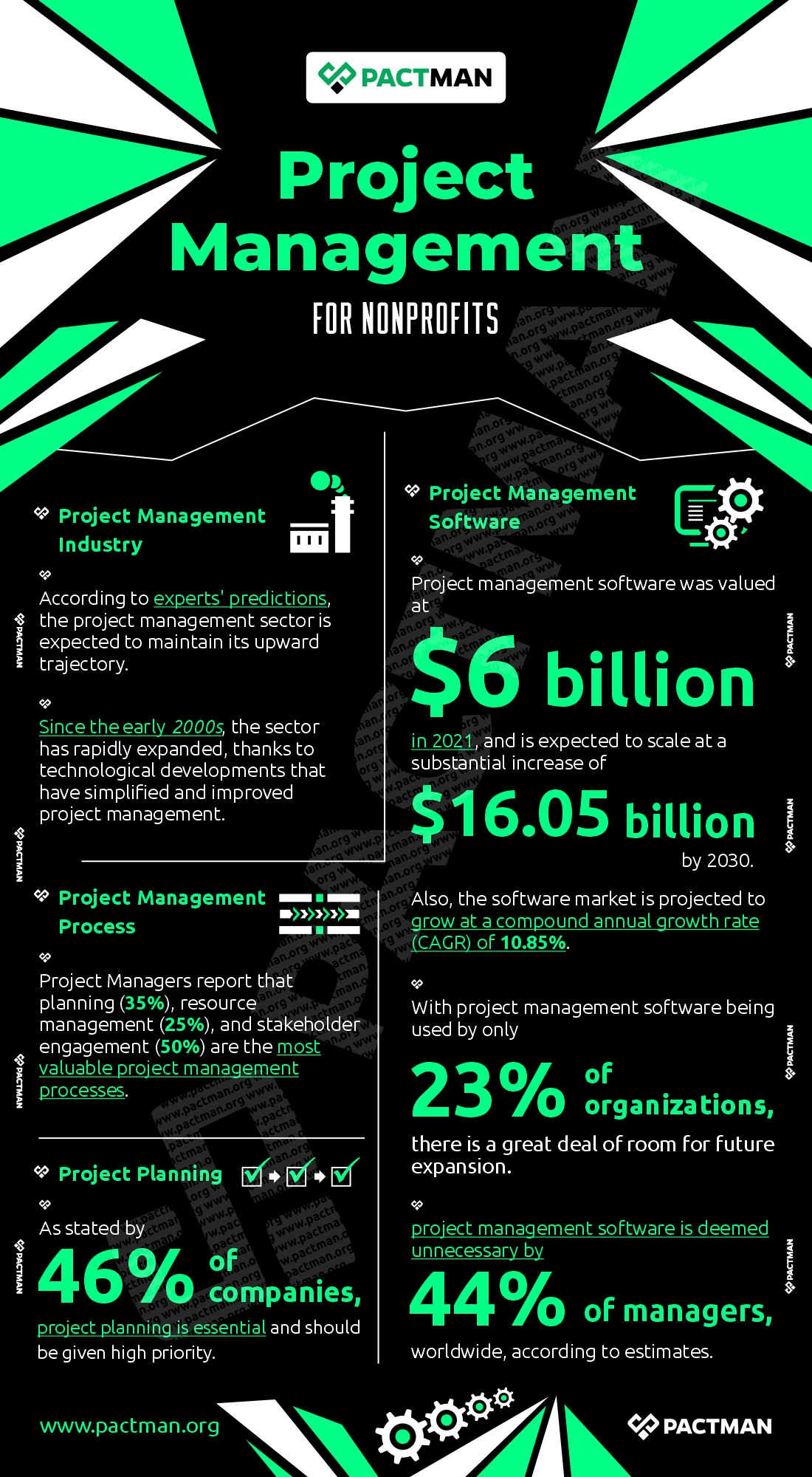

a. Project Management Software

In 2021, project management software was valued at $6 billion. By 2030, that amount is predicted to rise significantly to $16.05 billion. Also, it is anticipated that the software market will expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.68%.

Presently, there is a lot of space for future growth, as only 23% of organizations currently use project management software. However, according to estimates, 44% of managers globally believe that project management software is useless.

b. Project Management jobs

According to PMI’s recent Talent Gap report, project managers will need 2.3 million workers every year to cover unfilled jobs. Additionally, 87.7 million project management jobs would be required globally by 2027. This translates into additional work opportunities for project managers.

Remote project management is here to stay, as seen by the 91% of teams that report adopting virtual solutions for project management. This trend is likely to become more popular in the upcoming years. Furthermore, 69% of organizations place a high priority on developing project management skills to improve performance.

c. Project Completion

According to the PMI Pulse of the Profession study, 89% or more of projects are finished on time, under budget, and in accordance with scope in high-performing organizations. This illustrates how important effective project management is to achievement. Also, 43% of organizations reported that they frequently or consistently finish their projects on time and within budget.

d. Project Failure

67% of project failures are caused by insufficient attention to project management. Project failures most often occur for three reasons: unclear goals or objectives to measure success, poor communication, and inadequate planning (37%).

Also, investments in project management result in 28 times more savings for organizations than for those who don’t.

IV

Organizational Resilience: A Definition and Operationalization

Before 2020, the majority of foundations relied on steady assumptions. When awarding grants, they gave priority to:

- Predictability: Grant cycles are either annual or semi-annual.

- Accountability: Extensive evaluations of proposals, thorough financial plans, and strict compliance regulations.

- Control: Decisions are made top-down with little community involvement.

Although these systems provided structure and transparency, they were not adaptable enough to respond to shocks. Hence, this methodology was frequently criticized by nonprofit management researchers for being “process-heavy but impact-light.” Essentially, it implies being effective in paperwork but sluggish in execution. As a result, communities that were most in need during emergencies frequently had to wait too long for assistance. The pandemic instantly altered that calculation.

Presently, organizational resilience needs to be reinterpreted beyond mere endurance, especially in the nonprofit industry. As we all know, resilience is based on recuperation and rejuvenation rather than merely sustaining stress until burnout happens. Also, leaders and employees of non-profit organizations faced diminished morale. This was largely a result of tension between emergency objectives and established aims, and an uneven burden of duty as a result of the disruption’s increased demands.

Now more than ever, grantors must understand that incorporating recovery zones into expectations is crucial for performance optimization. There is a significant governance-operation gap when known threats, like pandemics, are not sufficiently planned for. Even if there is risk analysis at the board level, the organization is still exposed if the operational systems, such as the application, review, and reporting processes, are inflexible and avoid this analysis.

Furthermore, implementing adaptable project management techniques like Agile and Lean principles should be standardized as a long-term risk reduction strategy rather than just a stopgap measure used in an emergency.

In the history of charity, the pandemic was a turning point rather than a halt. The lessons learned at that time are still evident:

- Pay attention all the time.

- Learn nonstop.

- Adjust with boldness.

The future of social impact itself will be shaped by foundations that institutionalize these values, in addition to being able to withstand future storms.

V

The Development of Agile Grantmaking: Adopting Project Management Science

As earlier stated, the pandemic compelled charities to adopt business and technological concepts, especially Agile Project Management. For foundations and donors overseeing multi-national health, education, and relief initiatives, agile approaches, which are renowned for their iterative design, quick feedback loops, and flexible planning, proved essential.

a. Adopting Core Practices in Agile Grantmaking:

- Iteration versus Perfection: In order to enable real-time adjustment, funders can apply shorter, rolling award cycles.

- Cross-Functional Teams: Grantees, program officers, and community partners should work together through virtual task forces.

- Quick Learning Systems: Quarterly reports were superseded by dashboards and data visualizations.

Foundations applying agile principles can increase operational responsiveness at an exponential rate. By and large, this demonstrates that even established organizations are capable of acting with startup-like agility.

b. Building Resilience:

Secondly, as philanthropic organizations navigated a crisis, their compass became institutional, programmatic, and human resilient. But what does resilience actually entail?

- Institutional Resilience: To facilitate quicker decision-making, foundations reorganized internal governance. For instance, the Kresge Foundation gave program teams discretionary funds so they could support pressing community needs without waiting for board approval.

- Programmatic Resilience: Digital-first operations, hybrid grantmaking models, and contingency reserves became commonplace as programs were modified to adapt to changing realities.

- Human Resilience: Lastly, one major risk identified was staff fatigue. Prominent organizations made investments in psychological safety, flexible work schedules, and well-being initiatives to maintain performance in the face of uncertainty.

As the saying goes, “human adaptability is a function of organizational resilience.” Compared to foundations that stuck to pre-pandemic hierarchies, those that fostered trust, empathy, and internal cooperation fared better throughout the storm.

c. Including Crisis Management in Portfolio Risk

A McKinsey study on disaster response established the significance of the First 72 Hours Mandate. Essentially, the study highlights the necessity of providing committed leadership and care for impacted individuals right after a tragedy. This translates into immediate, unconditional actions for a grantmaking organization. A few examples include;

- providing grantees with unconditional releases of previously committed funds,

- proactively informing grantees of continuity assurances, and

- keeping lines of communication open to inquire about unmet needs.

All in all, the crisis demonstrated that the operational fiduciary duty, which entails the prompt and effective deployment of assets to halt community harm, is the highest fiduciary duty during a major disruption. Fundamentally, this differs from the conventional fiduciary obligation that is just concerned with endowment returns and asset protection. By and large, the goal must be to fulfill both responsibilities at the same time: maximizing impact velocity and protecting wealth.

VI

The Roadmap to Permanent Agile Grantmaking

The lessons learnt from the pandemic must be institutionalized through a multi-year, progressive organizational reform.

Phase I (6–12 months): Evaluation and Dedication

The first stage concentrates on defining the required change. In order to systematically discover and eliminate administrative waste, the organization must conduct an internal audit of all application and reporting processes, categorizing each step using an Agile/Lean framework. Also, to demonstrate a commitment to the values of collaboration and flexible funding, the foundation must legally embrace Trust-Based Philanthropy (TBP) as the long-term organizational default practice.

Phase II (12–24 Months): Operational Redesign

This stage entails constructing the agility infrastructure. Consequently, all employees of the Program and Project Management Office (PMO) are required to undergo Agile and Rapid-Cycle Learning (RCL) training. Also, to prepare the organization to proactively manage operational and financial unpredictability, the organization must create and include Scenario Mapping in annual portfolio planning.

Lastly, budgets must take transition support into account in establishing the structures and resources required for a responsible relationship closure.

Phase III (more than 24 months): Institutionalization and Governance

The last stage solidifies the adjustments at the level of governance. In addition to short-term outputs for evaluation, the board policy needs to be changed to formally embrace adaptive capacity measures and long-term systemic outcomes (social resilience).

Even more, standard grant agreements and standard operating procedures must specifically include operational flexibility measures. This may include changing project funds to general operating assistance and putting in place automatic renewals. Leadership must aggressively maintain the culture of adaptability and human resilience. This is by understanding that stagnation poses a serious obstacle to long-term relevance and influence.

VII

Moving Towards “Adaptive Philanthropy” in the Post-Pandemic Era

Adaptive philanthropy is an integrated paradigm that blends data-driven strategy, flexible finance, and human-centered management. According to academics, this will define the next phase of grantmaking. Without a doubt, this transition necessitates a mental shift in addition to operational adjustments. Even more, the organizations that thrive in volatility are those that see uncertainty as a design constraint, not a disruption. For grantmakers, this entails using every setback as a teaching opportunity and every danger as a springboard for resilience.

Here are crucial traits of flexible cooperation:

- platforms for shared data to promote transparency.

- collaborative frameworks for measurement.

- impact narratives jointly developed.

Adaptive philanthropy signifies a significant mental shift from short-term results to systemic resilience, from giving to strategic learning, and from solitary action to cooperative development.

Furthermore, 3 interrelated pillars form the foundation of adaptive philanthropy:

a. Ongoing Feedback and Education Systems

Conventional grant evaluations take place once a year or after a project, which is frequently too late to inform significant change. In adaptive philanthropy, this is replaced by real-time learning mechanisms.

How it operates:

- Current data: Funders keep an eye on events and results as they happen using dashboards, APIs, and digital reports.

- Community listening: Foundations incorporate feedback loops from the community through WhatsApp groups, digital town halls, and mobile surveys.

- Fast review cycles: Static board evaluations are replaced by “learning huddles” held either monthly or quarterly.

b. Responsive and Adaptable Capital

Secondly, rather than viewing financing as a fixed commitment, adaptive philanthropy views it as dynamic capital that can change and adapt to changing circumstances. Among the flexibility mechanisms are:

- General or unrestricted operating support: Giving grantees the freedom to set priorities.

- Rapid response funds: These are pools set aside for unforeseen circumstances (such as natural catastrophes or health outbreaks).

- Blended finance: Combining grants, loans, and equity for scalable impact .

- Rolling grant cycles: Applications are accepted all year long, rather than on a set date.

c. Collaborative Ecosystems

Lastly, interdependence, not independence, is what fosters adaptive generosity. Hence, grantors discovered that cross-sector cooperation increased results during the pandemic. Likewise, foundations collaborated with governments, businesses, and civil society to close gaps in local trust, supply chains, and information.

Here are collaborative ecosystem examples that stand out:

- Gavi and WHO co-led the COVAX program, which demonstrated global pooled finance for fair access to vaccines.

- The Philanthropy Southeast COVID-19 Response Fund brought together numerous foundations in the United States to coordinate relief efforts and minimize duplication.

- Through networks like the African Philanthropy Forum, African foundations worked together to share information and co-fund local resilience solutions.

Conclusion

In summary, the pandemic changed the definition of project management, risk assessment, and philanthropic outcome delivery. The foundations with the most flexible processes, open interactions, and technology-driven resilience were the ones that prospered, not those with the biggest assets. Also, the pandemic was a revelation as much as a disruption. It demonstrated how much the systems of philanthropy relied on stability and how fast they could adjust when it vanished.

Leading foundations of today are expanding on those lessons by embracing agile approaches, emphasizing resilience, and reframing what “results” actually mean. Project management in philanthropy is now about capacity, inventiveness, and bravery in the face of change rather than control. Going forward, the grantmaking ecosystem needs to approach results as transformation, resilience as strategy, and risk as insight. Uncertainty will always exist in the workplace. Therefore, a great organization is determined by how well it learns from its mistakes rather than how well it avoids them.

2 Responses