I

Introduction

When it comes to a grantmaking strategy, long-term impact is the cornerstone of any foundation’s or grantmaking organization’s mission. More than ever, the world is changing. Consequently, for organizations dedicated to long-term impact, relying exclusively on historical patterns or the “most likely” future is a formula for failure. Scenario planning is a potent instrument that aids foundations in investigating various futures so they can develop robust, flexible, and successful plans.

Scenario planning protects against this risk by offering four main advantages:

- Resilience: It evaluates your present plan under stressful circumstances that you want to avoid, such as a severe recession or political impasse.

- Relevance: It guarantees that your funding stays relevant by assisting you in identifying new demands that may not be apparent on your present planning horizon.

- Alignment: It improves internal alignment by giving staff and board members a consistent vocabulary and structure to debate drastically diverse possible realities.

- Optionality: It identifies strategic “hedges” required just for certain futures and “no-regrets” moves such as actions that are advantageous in all conceivable futures.

This guide will serve as a roadmap to make scenario planning easier to understand and demonstrate how to include it in your grantmaking approach.

II

Critical Statistics on Grantmaking Strategy and Scenario Planning

In this section, we will consider critical statistics on scenario planning and its relevance across organizations.

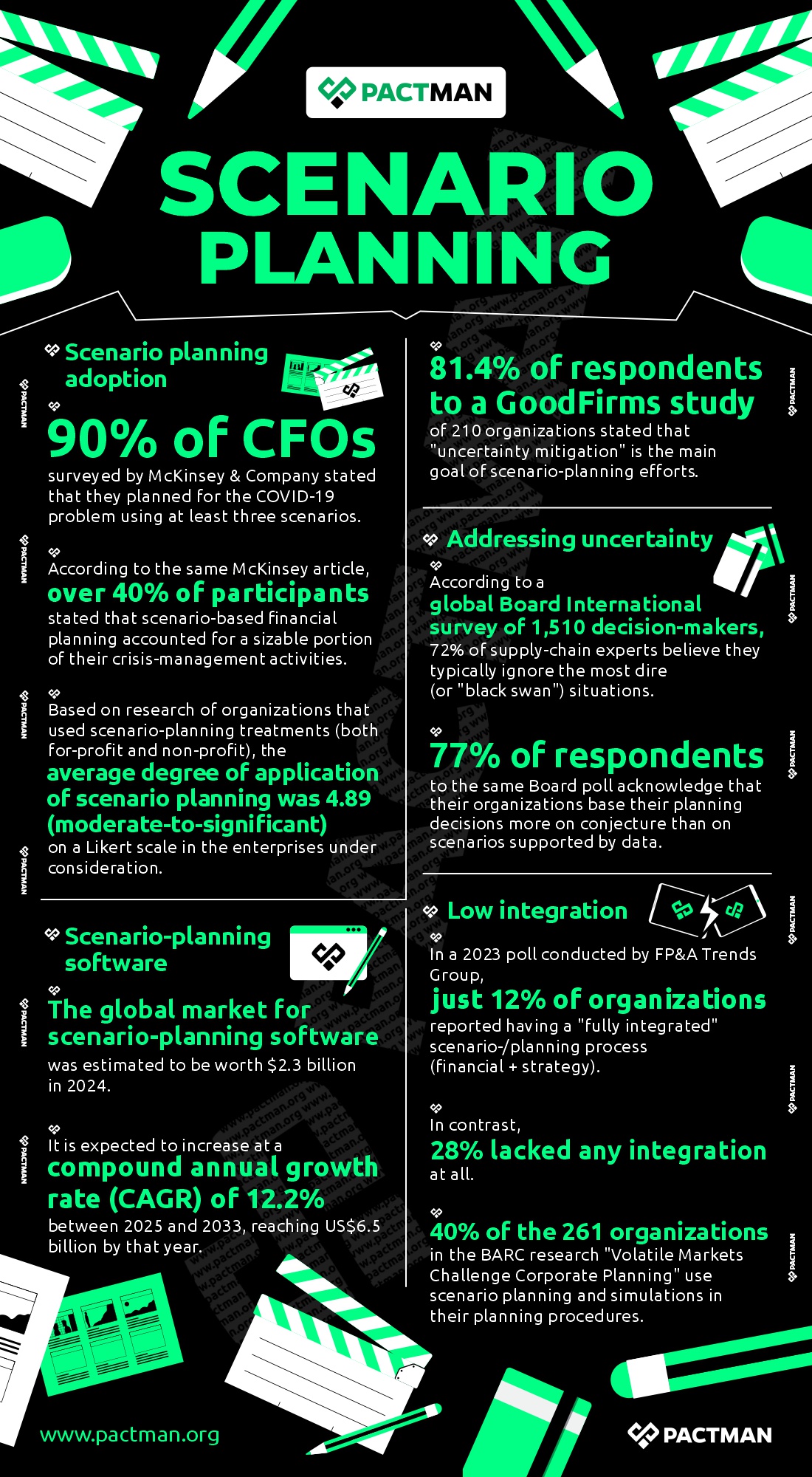

a. Scenario planning adoption

90% of CFOs surveyed by McKinsey & Company stated that they planned for the COVID-19 problem using at least three scenarios. According to the same McKinsey article, over 40% of participants stated that scenario-based financial planning accounted for a sizable portion of their crisis-management activities.

Also, based on research of organizations that used scenario-planning treatments (both for-profit and non-profit), the average degree of application of scenario planning was 4.89 (moderate-to-significant) on a Likert scale in the enterprises under consideration.

b. Scenario-planning software

The global market for scenario-planning software was estimated to be worth $2.3 billion in 2024. Also, it is expected to increase at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.2% between 2025 and 2033, reaching US$6.5 billion by that year.

c. Addressing uncertainty

81.4% of respondents to a GoodFirms study of 210 organizations stated that “uncertainty mitigation” is the main goal of scenario-planning efforts.

According to a global Board International survey of 1,510 decision-makers, 72% of supply-chain experts believe they typically ignore the most dire (or “black swan”) situations. Also, 77% of respondents to the same Board poll acknowledge that their organizations base their planning decisions more on conjecture than on scenarios supported by data.

d. Low integration

In a 2023 poll conducted by FP&A Trends Group, just 12% of organizations reported having a “fully integrated” scenario-/planning process (financial + strategy). In contrast, 28% lacked any integration at all.

40% of the 261 organizations in the BARC research “Volatile Markets Challenge Corporate Planning” use scenario planning and simulations in their planning procedures.

III

What Is Scenario Planning?

Scenario planning is a tactical tool for envisioning and preparing for various future iterations. The term Scenario planning was first created by military strategists and subsequently made popular by companies such as Shell in the 1970s. Essentially, it enables organizations to investigate “what if” scenarios to make better long-term decisions.

Note that scenario planning is not the same as making predictions. Rather, it is a systematic approach to planning and envisioning a number of conceivable futures. For a foundation, this entails creating two to four intricate stories, or “scenarios,” outlining potential changes to the political, economic, social, and technological environments that are pertinent to your goal. Scenario planning poses the question, “What could happen, and how would we respond?” as opposed to, “What will happen?”

For instance:

- What would happen if government support for nonprofit organizations drastically decreased over the course of five years?

- What if beneficiaries’ access to social services is altered by new technology?

- What if the communities we serve are severely impacted by climate change?

Using scenario planning, grantmakers may foresee dangers, spot opportunities, and make well-informed funding decisions rather than just respond to emergencies. Despite working on problems that take decades to resolve, grantmakers must function in extremely dynamic situations.

By and large, grantmaking organizations can benefit from scenario planning in various ways:

- It allows the board and employees to reevaluate their future-oriented presumptions.

- It highlights possible hiccups that can cause the current grant portfolio to fall apart (e.g., a sudden economic downturn, a new regulation).

- It highlights underutilized regions where investment could have a disproportionately significant influence in certain future scenarios.

- A foundation will be more flexible and equipped to change course if the environment changes

IV

A Six-Step Grantmaking Strategy Process in Scenario Planning

All in all, six distinct consecutive phases can be adopted to apply scenario planning to grantmaking.

1. Describe the Focus Question and Scope

First, you must clearly identify the scope of your research before you begin. Which uncertainty is most important to your foundation? For instance, an education foundation might ask focus questions such as:

- “What are the most plausible futures for K-12 public education funding and delivery over the next 10 years?

For a climate foundation:

- “How will technological innovation and global political cooperation combine to affect our carbon reduction goals by 2035?”

If housing is the primary concern:

- “How will the intersection of remote work trends and municipal zoning laws reshape affordable housing needs over the next five years?”

By and large, it is imperative to establish the time horizon (5 to 15 years) and the geographic scope (local, national, or global) in advance.

2. Determine the PESTEL Framework’s Principal Drivers of Change

Next, list the main factors that will influence change in your organization’s focus area. Essentially, the PESTEL framework is a fantastic place to start. To begin with, make a list of all the drivers that are both uncertain and essential to your aim.

| Driver | Description | Grantmaking Example |

| Political | Policy shifts, regulatory changes, elections. | A new administration introduces universal childcare. |

| Economic | Interest rates, inflation, job markets, and wealth inequality. | A prolonged global recession limits corporate giving. |

| Social | Demographic changes, cultural values, and public trust. | Increased skepticism toward institutional philanthropy. |

| Technological | AI, automation, biotechnology, connectivity. | Generative AI revolutionizes educational content creation. |

| Environmental | Climate events, resource scarcity, and sustainability efforts. | Extreme heat events disrupt local food supply chains. |

| Legal | Court rulings, international treaties, and labor laws. | A Supreme Court ruling affects voter registration efforts. |

3. Identify the Critical Uncertainties

Among the two drivers mentioned in Step 2, which are the most important (they have the most influence on your plan) and the least certain (they are the least predictable)? For the most part, your scenario matrix’s axes will be formed by these two drivers. They ought to be unrelated to one another and have different, well-defined options (e.g., High vs. Low).

Example of Critical Uncertainties:

- Technology (Axis 1): Adoption Rate of AI (Slow/Incremental vs. Fast/Disruptive)

- Politics (Axis 2): Level of Bipartisan Collaboration on Social Issues (High/Collaborative vs. Low/Fractured)

4. Create the scenarios (the 2×2 matrix)

Also, you can create four different, believable future settings by plotting your two essential uncertainties on a 2×2 grid.

| Axis 2: Collaborative Politics (High) | Axis 2: Fractured Politics (Low) | |

| Axis 1: Fast AI Adoption (High) | Scenario A: Automated Consensus | Scenario B: Digital Divide |

| Axis 1: Slow AI Adoption (Low) | Scenario C: Slow, Steady Progress | Scenario D: Stagnant Status Quo |

Now comes the creative and critical work:

- For each of the four situations, write the narrative.

- Assign them names that evoke strong feelings (such as the aforementioned instances) and explain how the world of five or ten years from now came to be.

- Attention to Narrative: How would you describe your experience as a staff member, grantee, or recipient in that world?

- Include Additional Drivers: To further develop the stories, use the additional PESTEL drivers (from Step 2) as illustrative information.

5. Examine the Challenges in Your Present Grantmaking Approach

This is the point at which you relate the situations to your ongoing work. In each of the four situations, have your group ask critical questions:

- Efficient: What might the performance of our present grant portfolio be in the future?

- Vulnerabilities: Which aspects of our plan might not work or become relevant?

- Surprises: If we didn’t look in that direction, what opportunities would we miss?

This stress test assists you in determining the blind spots in your present approach.

6. Include Scenarios in the New Approach

You can now modify your grantmaking to increase resilience in light of the stress test results.

- Determine “Robust” Techniques: In each of the four cases, these are sensible acts that yield favorable outcomes. (for instance, supporting adaptable organizations with excellent digital capabilities). Essentially, these are your “no-regrets” moves.

- Determine “Hedge” Techniques: These are investments created expressly to guard against a possible loss in one or two situations. (For instance, funding policy advocacy to prevent possible political division).

- Get “Trigger” Indicators Ready: What are the early indicators that the likelihood of one scenario is increasing relative to the others?

To track these indications, establish a system and define metrics (e.g., “If new federal spending on X is less than $100M this year, Scenario D is gaining ground.”). This enables effective grantmaking fund pivoting.

Conclusion

Scenario planning doesn’t have to be a major, costly makeover. The goal is to prioritize learning over perfection. By and large, the conversations and insights that are obtained during the process are more valuable than the scenarios. It involves allowing your team to see the possibilities.

When you embrace this method, your foundation shifts from a reactive to a proactive approach, guaranteeing that your precious resources are used to have the most impact possible, no matter what happens in the future. Through scenario planning, grantmakers may confidently welcome uncertainty. In a society where societal demands change quickly, the most successful foundations are those that are ready for the future rather than those that have perfect future predictions.

3 Responses