I

Introduction

An operations plan primarily refers to the goals or future outcomes (results) that individuals, groups, and organisations desire and strive to achieve. Goals can be implicit or explicit, vague or clearly defined, and self-imposed or externally imposed, among other things. However, regardless of their format, they help to organise employees’ time and effort.

The strategic plan details the organisation’s future direction, but the operations plan specifies what gets done now through goals to be achieved in the upcoming year. Nevertheless, whether it’s an operational, tactical, or implementation plan, execution is crucial. As the saying goes, “No worthwhile strategy can be planned without considering the organisation’s ability to execute it.”

One of the reasons why the operations plan receives less attention is because it is a logical continuation of the strategic plan, in which significant intellectual resources have been invested. This article will consider the importance of an operations plan for nonprofit organisations and the processes.

II

What is an Operations Plan?

An operations plan takes into account the process of identifying the precise tasks that must be accomplished, setting a deadline for their completion, designating accountability for each task and determining the necessary financial and human resources. It also includes choosing the best organisational structure, identifying the information systems that will be needed, defining the metrics by which success or competition will be judged, and other operational details.

By and large, The leader’s main duty in the operations plan is to supervise the smooth transition from strategy to operations. Hence, he/she must establish the objectives, direct the operating reviews that unite individuals around the operating plan, and connect the specifics of the operations process to the people.

In the face of countless options, the leader must make prompt, astute decisions and trade-offs. This includes engaging in lively discourse that reveals the truth. At the same time, it requires training workers on how to accomplish these goals.

However, the presence and involvement of the leader is not the only need. The strategy must be developed with input from everyone responsible for carrying out the operations plan.

Keep in mind that nonprofit organisations employ fewer people, and have a few full-time employees or none at all as they tend to leverage the help of volunteers. Because of this, only the important, high-impact goals are included in the operations plan. If this means that a given department only has one, two, or no goals at all, then no worries.

III

Critical Statistics to Consider

This section will consider critical statistics that highlight the importance of operations plans for organisations.

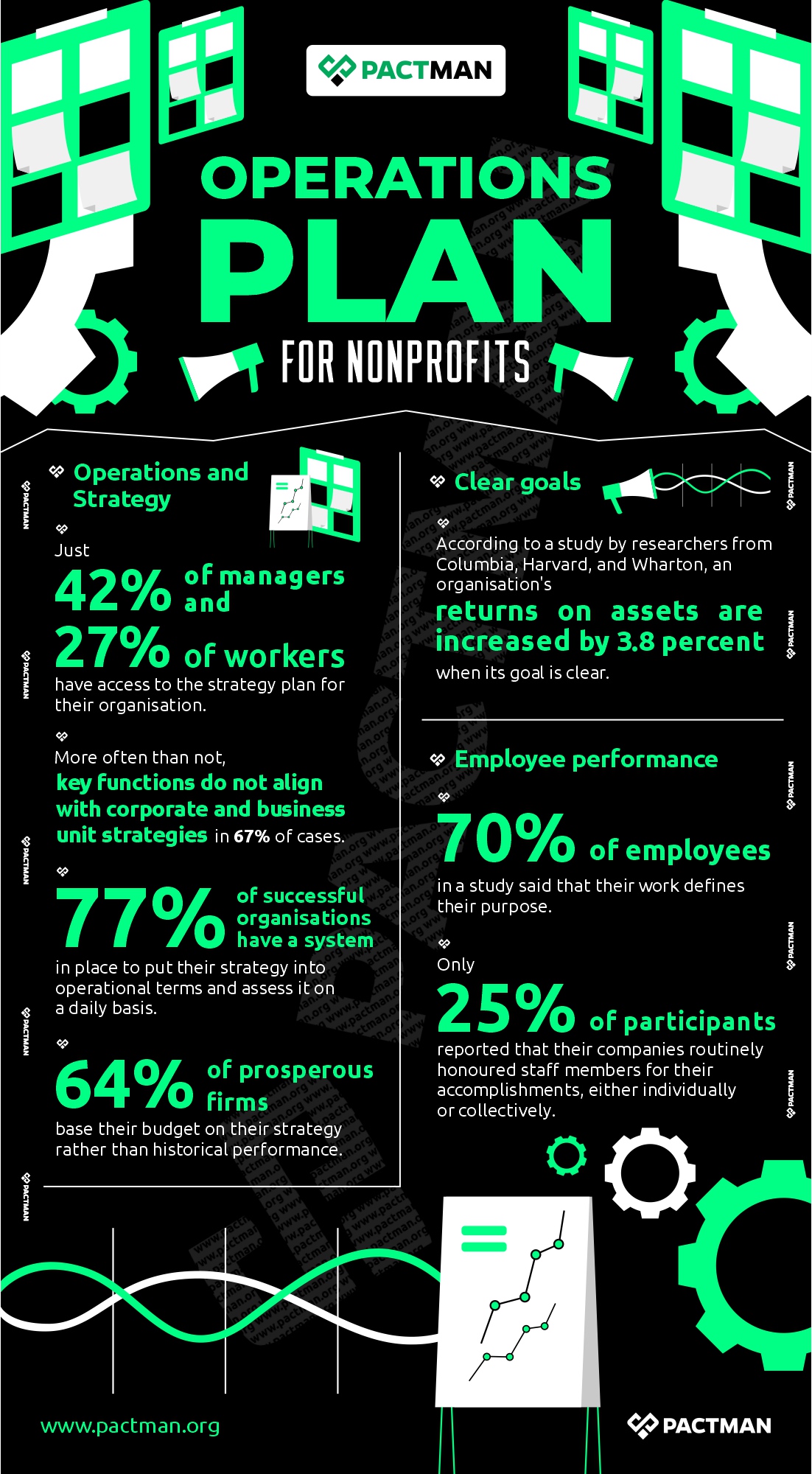

1. Operations and Strategy

Just 42% of managers and 27% of workers have access to the strategy plan for their organisation. More often than not, key functions do not align with corporate and business unit strategies in 67% of cases.

77% of successful organisations have a system in place to put their strategy into operational terms and assess it daily. Also, 64% of prosperous firms base their budget on their strategy rather than historical performance.

2. Clear goals

According to a study by researchers from Columbia, Harvard, and Wharton, an organisation’s returns on assets are increased by 3.8 per cent when its goal is clear.

3. Employee performance

70% of employees in a study said that their work defines their purpose. Also, only 25% of participants reported that their companies routinely honoured staff members for their accomplishments, either individually or collectively.

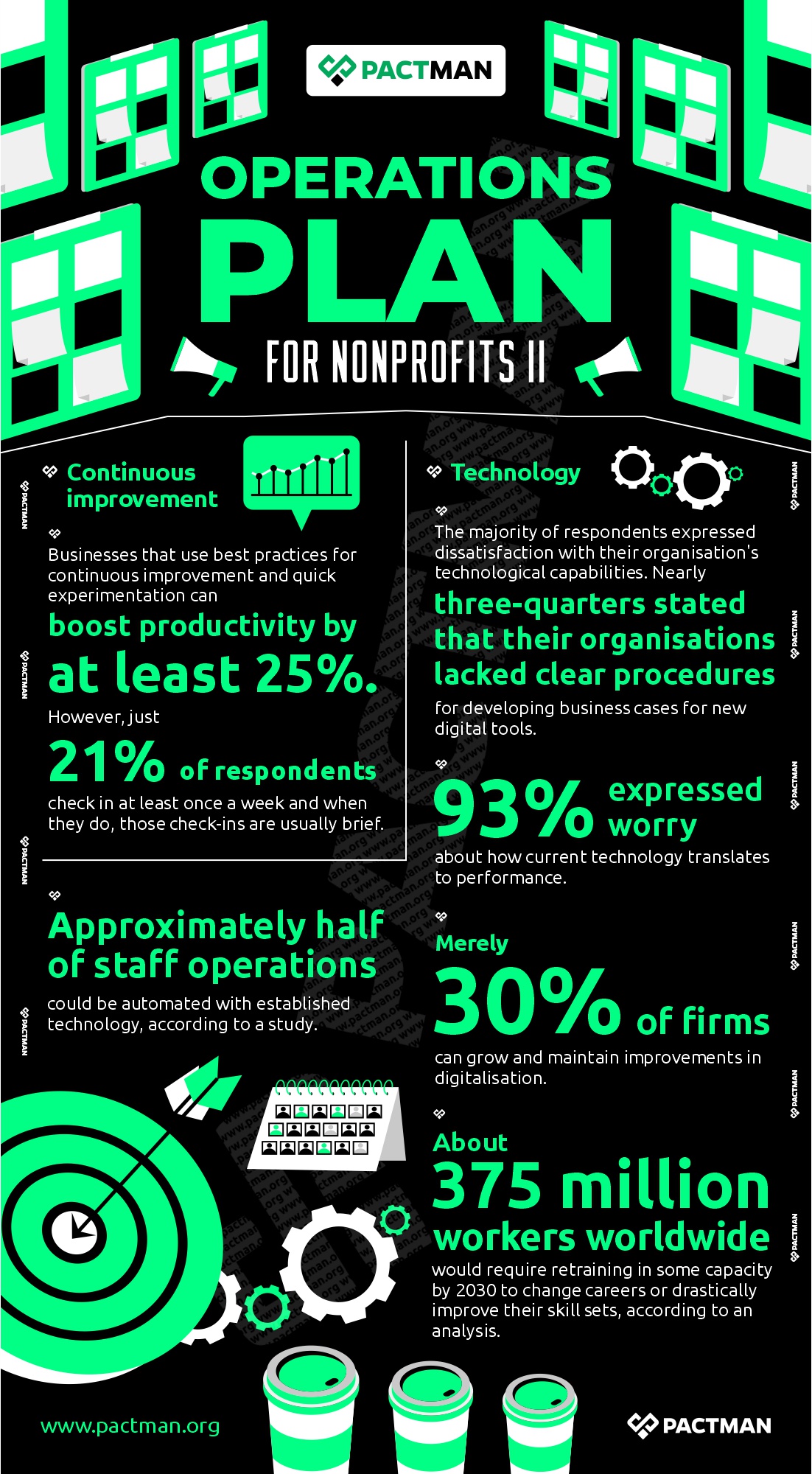

4. Continuous improvement

Businesses that use best practices for continuous improvement and quick experimentation can boost productivity by at least 25%. However, just 21% of respondents check in at least once a week and when they do, those check-ins are usually brief.

5. Technology

The majority of respondents expressed dissatisfaction with their organisation’s technological capabilities. Nearly three-quarters stated that their organisations lacked clear procedures for developing business cases for new digital tools, and 93% expressed worry about how current technology translates to performance. Merely 30% of firms can grow and maintain improvements in digitalisation. Also, approximately half of staff operations could be automated with established technology, according to a study.

About 375 million workers worldwide would require retraining in some capacity by 2030 to change careers or drastically improve their skill sets, according to an analysis.

IV

What to Consider When Creating an Operations Plan

Achieving their aims while preserving operational effectiveness presents special difficulties for nonprofit organisations. However, an operations plan can guarantee team alignment and effective resource allocation. Essentially, it serves as a guide for converting the nonprofit’s strategic goal into concrete actions.

Except for board-related objectives, the staff typically creates the operations plan. It is created in a more methodical, sequential manner to represent the two aspects of goals and budget. Also, the objectives of the operations plan outline what will be done in the upcoming year to produce noteworthy outcomes right away.

This guide offers a thorough rundown of the priority areas when creating an operations plan that works for your nonprofit.

1. Establish Goals Using Organisational Chart

Since success depends on responsibility, the first step is to identify who will be in charge of accomplishing the objectives. A simple method is to compile a list of every individual who works for the organisation, whether they are paid or not, volunteers or employees, and begin from there. Examine your plan again to ensure there are people to support each component. If you have personnel covering every aspect, then everything is OK.

However, how can one determine if they have covered every base? What if there is a base that needs to be covered but no one is set up to handle it? To be certain, it is best to create an organisational chart. As is typically the case with traditional systems, you create the organisational chart around functions that are essential to the organisation’s operations. It doesn’t matter if they are not staffed by individuals. In practice, departmental boundaries and job titles mean little in many nonprofit organisations because employees’ responsibilities sometimes span several functions. Also, since most nonprofit organisations have a lean organisational structure, it is typical for employees to perform a variety of tasks. Consider the numerous smaller nonprofit organisations that rely on donations from the public.

The identification of development functions in the organisational structure increases the likelihood that fundraising objectives will be stated. In this case, whether or not individuals are working in that area, your organisational chart serves as a reminder of what has to be done in terms of functions.

2. Prioritise Budget

Although there are several styles for the budget, there is only one general rule: a budget should not exceed one or two pages. Also, be aware that soliciting too many ideas could result in an overly complex format. Hence, what could have been a straightforward presentation with three or four columns becomes impossible to understand.

Any budget summary that is provided to the board should, at the very least, provide sufficient details to address these four queries:

- How much has been spent this fiscal year thus far?

- What is the current fiscal year’s approved budget?

- How is the current fiscal year expected to conclude?

- What distinguishes a projection from a budget?

By and large, these four viewpoints help the reader comprehend the fundamental financial situation.

The forecast, which is frequently overlooked, is especially significant. Unfortunately, year-to-date comparisons with percentages and a wealth of information are the most popular format. This strategy has emerged mainly because board members who are focused on making money feel at ease with publicly traded companies using quarter-to-quarter comparisons. Another possibility is that this format is the default for the software being used. However, such information might be highly distracting for a nonprofit.

Generally speaking, the more information that is supplied and benefits the reader, the better. Nevertheless, there is a limit. Giving too much information can be dangerous since some people might not be able to understand all the specifics. It is advisable to start a conversation in the proper format at the absolute minimum rather than the maximum. More often than not, only the four-column approach—year-to-date, budget, forecast, and variance—is needed.

-

Balance sheet

Also, it is acceptable for certain organisations to include a balance sheet in their financial presentation. This can be rather beneficial. However, it’s a good idea to keep in mind that balance sheets are complicated and frequently hard to comprehend. Reducing the balance sheet to its most basic components achieves the goal of simplicity, which is always a good idea.

Usually, the budget’s bottom section displays the condensed balance sheet. It’s also a good idea to keep in mind that periodically creating balance sheets during the fiscal year can be a time-consuming task with little return, particularly for smaller nonprofits.

-

IRS Form 990

Using the IRS Form 990 categories is one of the simplest ways to create a budget. It makes it easy to compare your organisation to its counterparts and provides a reliable medium for discussing your financial status. It is completely suitable for usage at the whole board level and produces a comprehensive perspective that includes the balance sheet, all on less than one page.

The budget structure is already established since agencies that must submit Form 990 will have a methodology in place for handling this. To put it briefly, it is accessible and convenient for the majority.

3. Establish Governance

There are exceptions to the generalisation that an institution can be seriously harmed by a poorly performing board or that an effective board equates to an effective corporation. Though there isn’t enough conclusive evidence to support the idea that boards and successful organisations are causally related, common sense dictates that a stronger board can enable an organisation to realise its full potential while a dysfunctional board can hinder it.

There are further justifications for being concerned about governance quality. Some board members legitimately argue that teams make better decisions than individuals.

While the exercise of collective responsibility through a board can slow down some kinds of decision-making, it adds levels of protection and judgment, which serve as checks and balances.

-

Measure board performance

How effectively do board members and the boards they serve carry out their official duties? Without a doubt, boards can have an impact on the organisation’s operations.

The basic fact is that most people want nonprofit boards to be accountable and effective, but knowing how to do this has always been a challenge. The same is true for underperforming boards. In addition, there aren’t specific repercussions for underperforming board members. A member of a board who has the power to influence a specific outcome or raise a sizable sum of money is invaluable.

To begin with, board structure should be based on inclusion, which can be accomplished by reducing the size of the executive committee and aiming for a smaller, more straightforward board. In addition, the board’s duties should include self-evaluation continuously.

-

Create a high-performing board team

The keys to better governance include hiring, training, and mentoring. Creating a high-performing board team entails creating a team that is prepared, willing, and able to concentrate on the main issue. To achieve this, everyone should be aware of the organisation’s primary objectives and goals. Oftentimes, that’s where boards and organisations frequently run into serious problems. They forget that achieving the organisation’s specific objectives is the primary goal of governance.

The board serves as a tool, not an end in and of itself. It makes no difference if board meetings are engaging or directors are content if the board does not fulfil its promise to accomplish its objective. All in all, effective boards make meaningful use of their limited time and expertise because they understand that they cannot avoid accountability and authority.

4. Prioritise Delegation

According to Carl Larson and Frank LaFasto, every member of any successful team must understand at the outset what he or she will be held accountable for and measured against in terms of performance. Without clear roles and accountabilities, all efforts become random and haphazard.

Generally speaking, clearly defined roles and accountabilities are essential to a results-driven structure. In the governance plan’s delegation section, the obligations cover distinct roles and responsibilities. Clarity and concreteness are essential components of standards of excellence. The extent to which standards are clearly and concretely articulated determines the eventual likelihood of the standards being met. By and large, this is considerable with clearly defined responsibilities and rules.

Being a board member is a challenging task. Duties are simply jobs—neither more nor less. If left unclear, a lot of board members are likely to mistake the board’s responsibilities for each board member.

Therefore, the board should only be responsible for the tasks to which it plans to hold itself. Also, the authority that the board gives to the team and committee must be carefully considered in the bylaws’ delegation section. The extent to which an executive committee can function effectively is largely determined by the boundaries of its power. Additionally, the board can empower a staff-level committee composed of board members if they so desire.

Conclusion

The success of a nonprofit depends on having a strong operations plan. It guarantees alignment, maximises resources, and improves responsibility by offering a clear pathway. Although the creation of an operations plan calls for cooperation and work, the advantages greatly exceed the drawbacks. Keep in mind that an effective operations plan changes as your nonprofit’s requirements and external conditions do. Your organisation will stay on course to fulfil its objective if there are regular updates and assessments.

2 Responses