I

Introduction

Global spending on diversity, equity, and inclusion is expected to increase from $7.5 billion in 2020 to $15.4 billion by 2026. However, the return on this investment remains elusive for many foundations. According to the McKinsey “DEI Lighthouse” research, five success elements are shared by the most successful initiatives: a meaningful definition of success, accountable leadership, context-specific solutions, thorough tracking, and a sophisticated understanding of core causes.

Redefining success for grantmakers necessitates a change from assessing activities (the amount of money awarded) to measuring outcomes (the real changes in systems for the individuals involved).

II

Critical Statistics on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

In this section, we will consider critical statistics on diversity, equity, and inclusion and their impact.

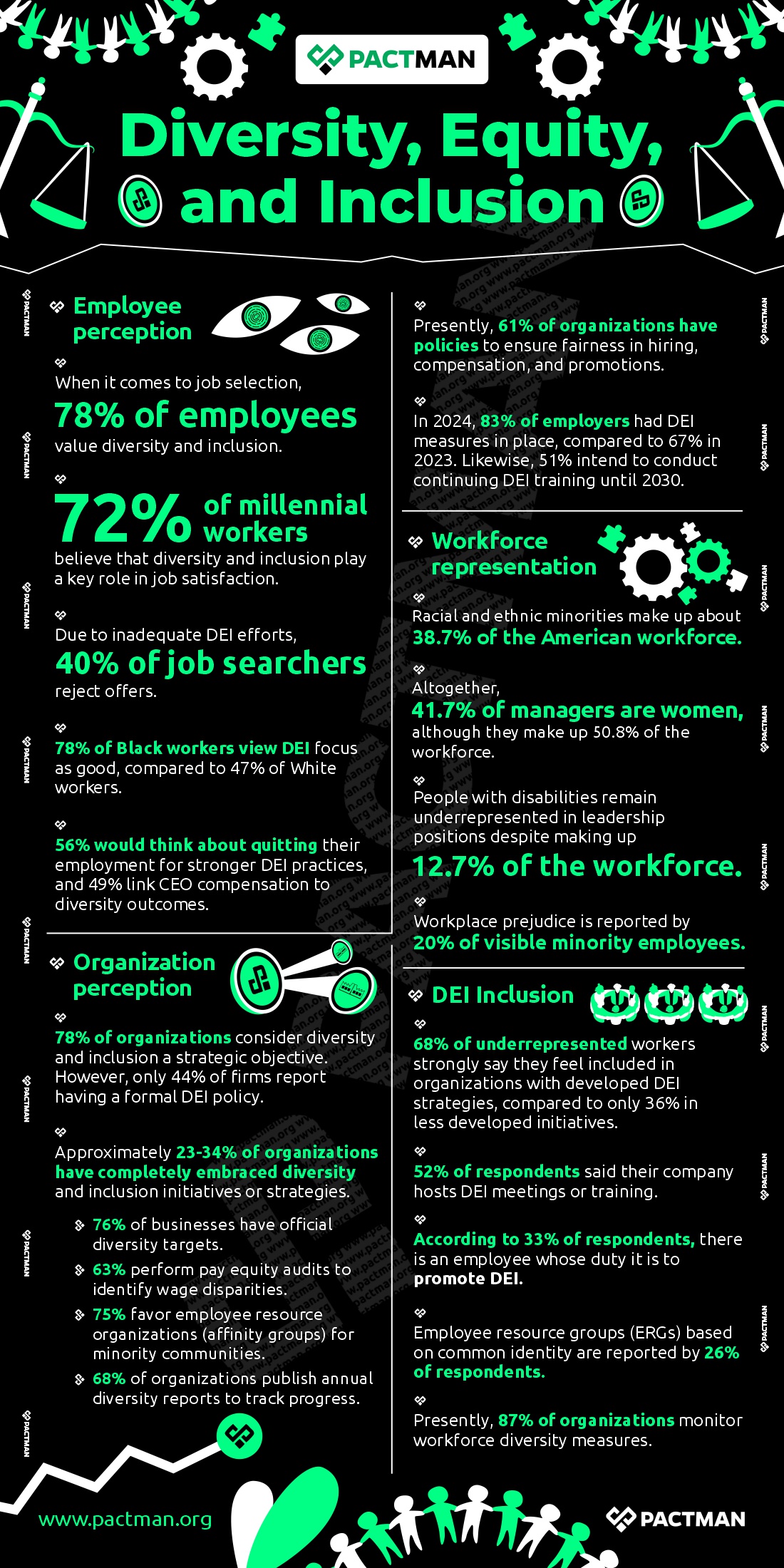

1. Employee perception

When it comes to job selection, 78% of employees value diversity and inclusion. Also, 72% of millennial workers believe that diversity and inclusion play a key role in job satisfaction.

Due to inadequate DEI efforts, 40% of job searchers reject offers. Even more, race, gender, and political affiliation all have a substantial impact on how people view DEI. For instance, 78% of Black workers view DEI focus as good, compared to 47% of White workers.

56% would think about quitting their employment for stronger DEI practices, and 49% link CEO compensation to diversity outcomes.

2. Organization perception

78% of organizations consider diversity and inclusion a strategic objective. However, only 44% of firms report having a formal DEI policy. Approximately 23-34% of organizations have completely embraced diversity and inclusion initiatives or strategies.

- 76% of businesses have official diversity targets.

- 63% perform pay equity audits to identify wage disparities.

- 75% favor employee resource organizations (affinity groups) for minority communities.

- 68% of organizations publish annual diversity reports to track progress.

Presently, 61% of organizations have policies to ensure fairness in hiring, compensation, and promotions. In 2024, 83% of employers had DEI measures in place, compared to 67% in 2023. Likewise, 51% intend to conduct continuing DEI training until 2030.

3. Workforce representation

Racial and ethnic minorities make up about 38.7% of the American workforce. Altogether, 41.7% of managers are women, although they make up 50.8% of the workforce. Also, people with disabilities remain underrepresented in leadership positions despite making up 12.7% of the workforce. All in all, workplace prejudice is reported by 20% of visible minority employees.

4. DEI Inclusion

68% of underrepresented workers strongly say they feel included in organizations with developed DEI strategies, compared to only 36% in less developed initiatives. Also, 52% of respondents said their company hosts DEI meetings or training.

According to 33% of respondents, there is an employee whose duty it is to promote DEI. Even more, employee resource groups (ERGs) based on common identity are reported by 26% of respondents. Presently, 87% of organizations monitor workforce diversity measures.

III

Common Pitfalls in Measuring Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion and How to Avoid Them

Measuring diversity, equity, and inclusion is now crucial for legitimate, successful philanthropy. However, many organizations struggle, not because DEI is undervalued but because their methods of evaluating it compromise impact, accountability, and transparency. In order to help foundations and grantmakers transition from symbolic reporting to meaningful, equity-oriented learning and decision-making, we will examine the most prevalent measurement errors in this section and provide specific strategies for avoiding them.

1. Converting DEI to Surface-Level Diversity Measures

The Pitfall:

Organizations frequently place a lot of emphasis on quantifying demographic representation, such as the number of women, people of color, or members of other groups, without delving further into the true meaning of those figures. This gives the impression that progress is being made even in the absence of significant change.

What Makes It a Problem:

Individuals’ participation in decision-making, retention of power, and equal outcomes are not revealed by representation alone. Reporting only diversity counts may conceal disparities in inclusion (a real sense of influence and belonging) and equality (fair access to opportunities).

How Not to Do It:

- Extend DEI assessment beyond headcounts by incorporating diversity and inclusion metrics like experience metrics, leadership pathways, retention rates, and decision-making impact.

- To comprehend context and lived experience, combine quantitative data with qualitative information from surveys, interviews, and stories.

- While interpreting numerical data, consider the question, “Who benefits?” “Who Doesn’t? Why, then?

2. Disregarding Intersectionality When Analyzing Data

The Pitfall:

Secondly, a lot of measuring frameworks focus on specifically identifying characteristics, such as gender or ethnicity. This does not adequately convey how people’s experiences and obstacles are shaped by the intersections of multiple identities.

What Makes It a Problem:

If a person’s racial identification creates an additional layer of marginalization, they may be counted within a gender category but remain invisible in equality talks. For instance, women of color frequently have different obstacles than white women or men of color, yet these subtleties are overlooked by straightforward measurements.

How to Prevent It:

- Gather broken-down data so that intersectional analysis can be performed (e.g., gender × race × disability).

- Rather than analyzing identity categories separately, develop measurements that can capture the compounding consequences of disadvantage.

- Incorporate qualitative insights into how various identities interact in real-world contexts.

3. Emphasizing quantitative data at the expense of experience.

The Pitfall:

Focusing solely on numerical measures, such as percentages of diverse recruits, can generate a false sense of accomplishment by ignoring how individuals feel, belong, and engage.

What Makes It a Problem:

Inclusion cannot be fully understood in terms of statistics: it is essentially subjective, whether people feel valued, safe, heard, and have the ability to influence decisions. Basic surveys may fail to capture this complexity unless they are intelligently structured.

How to Prevent It:

- Incorporate metrics into frequent inclusion surveys, focus groups, and open-ended feedback methods.

- Use techniques like experience audits and sentiment analysis to determine whether diverse participants feel empowered and respected.

- Analyze data using narratives, patterns, and community input.

4. Inadequate Measurement Framework Standardization

The Pitfall:

Different teams or initiatives may measure DEI differently in the absence of agreed-upon definitions and uniform frameworks, which could result in inconsistent outcomes.

What Makes It a Problem:

It is challenging to measure progress, evaluate solutions, or compare performance across programs, partners, or years due to inconsistent definitions of equity and inclusion.

How to Prevent It:

- Create precise frameworks and standards for measuring DEI that are consistent with your mission and strategic goals.

- Create a standard vocabulary and set of indicators for each team and project.

- Analyze and improve measurements over time to take corporate priorities and changing understanding into account.

5. Allowing Data Privacy and Trust Concerns to Prevent Involvement

The Pitfall:

Gathering private information on a person’s race, gender identity, sexual orientation, disability, etc., poses privacy issues. Employees or community members can be unwilling to offer correct information if it is not handled carefully.

What Makes It a Problem:

Inaccurate or incomplete data might understate injustices and distort insights. Even worse, it can undermine trust, particularly among those whose opinions are most important for measuring equity.

How to Prevent It:

- Ensure that the gathering of data is ethical, voluntary, and anonymous.

- Clearly explain how data will be utilized, safeguarded, and reported.

- Rather than imposing classifications, offer choices for self-identification.

6. Viewing DEI Assessment as a One-Time Task

The Pitfall:

Some organizations simply initiate DEI measuring initiatives once or infrequently, then neglect to monitor or adjust in response to findings.

What Makes It a Problem:

DEI is a dynamic process that is constantly changing. Without iterative learning, organizations are unable to adjust their strategy in response to what works and what doesn’t. Static assessment also fails to record progress over time.

How to Prevent It:

- For data collection, analysis, and reflection, use continuous measurement cycles spaced out at regular intervals.

- Create feedback loops that directly link strategy modifications and resource choices to measurement.

- In order to improve learning and responsibility, consider measuring as a component of an adaptive management approach.

7. Inadequate funding for DEI measurement tasks

The Pitfall:

Also, many foundations and grantmakers pledge to support DEI objectives without allocating sufficient financial, human, and analytical resources for reliable measurement and learning.

What Makes It a Problem:

Infrastructure is necessary for measurement, including data systems, knowledgeable analysts, and secure platforms. Without these, the results will be inadequate or inconsistent. Even more, DEI measurement may become flimsy and untrustworthy due to inadequate resources.

How to Prevent It:

- Set up a specific budget and staff to measure DEI.

- When necessary, hire outside experts or develop internal capacity through training.

- Measurement should be viewed as a strategic investment rather than an administrative burden.

8. Bias or Context Ignorance Leads to Misinterpretation of Data

The Pitfall:

Lastly, metrics are only as good as the analysis that interprets them, which is the trap. Hence, data can be misinterpreted or exploited in the absence of context. For instance, one could perceive an increase in hiring diversity without considering retention or inclusion statistics.

What Makes It a Problem:

Biases among analysts might influence interpretation, resulting in incorrect conclusions or poor choices. Furthermore, metrics might be deceptive if the organizational context, such as structural impediments or historical disparities, is ignored.

How to Prevent It:

- Educate analysts and decision-makers on bias awareness and DEI contextual interpretation.

- To shed light on context, combine quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

- Before taking action, challenge interpretations through peer learning and stakeholder evaluation.

IV

A Handbook for Grantmakers

Embedding Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion is a multi-phase structural path for grantmaking organizations that seek to progress from internal alignment to community-centered responsibility. Here are seven essential steps for foundations to become fair partners.

Step 1: Internal Alignment – The “Mirror” Process

Before a foundation can effectively disrupt external inequality, it must first hold up the mirror to its own leadership and staff.

- Diversify Decision-Makers: Ensure the board and program officers reflect the demographics of the communities served. For example, the Ford Foundation significantly increased representation by removing elite-university requirements and using gender-neutral job descriptions.

- Intentional Recruitment: Define specific characteristics for a diverse board (race, gender, geography, expertise) and set target percentages for members who are beneficiaries or grantees.

Step 2: Outreach Reform – Disrupting the Vicious Cycle

Also, traditional funding often flows to organizations with existing resources and relationships, leaving grassroots groups on the sidelines.

- Open the Gates: Move beyond invitation-only processes. If continuing with invitation-only, poll community foundations and local intermediaries to identify emerging, frontline organizations.

- Proactive Engagement: Use media outlets that serve diverse communities and explicitly invite under-resourced organizations to apply, reducing the reliance on inside networks.

Step 3: Application Accessibility – Reducing the Grantee Burden

Cumbersome application processes favor well-funded nonprofits with dedicated grant-writing staff.

- Streamline Paperwork: Keep the application time under 10–15 hours and accept documents in the format grantees already use (e.g., existing budgets or bios).

- The Common App Model: Sector-wide adoption of a single application platform could save nonprofits billions annually in administrative costs.

Step 4: Operationalizing Trust – The Relational Model

Trust-based philanthropy shifts the power dynamic by assuming that nonprofit leaders know best how to deploy resources.

- Multi-Year, Unrestricted Funding: This is the gold standard for equity, providing the stability needed for long-term planning and staff retention.

- Verbal Check-ins: Replace rigid, voluminous written reports with conversational check-ins that focus on relational learning rather than compliance.

Step 5: Asset-Based Capacity Building – Support Beyond the Check

Furthermore, foundations should provide technical assistance (TA) that builds organizational muscle without reinforcing deficit-based stereotypes.

- Asset-Based Framing: Pivot from fixing problems to investing in strengths. Define communities by their dreams and existing contributions rather than their gaps or risks.

- Data for Equity Projects: Pair grantees with data experts to identify internal inequalities using power maps and bias checks. This TA helps organizations move beyond simple headcounting to understanding true community value.

Step 6: Redefining Success – The SROI Narrative

To justify equity investments to boards, leaders must use the Social Return on Investment (SROI) framework to monetize social benefits.

- The Calculus of Impact: Calculate the ratio of total social value to investment. For example, a 3:1 ratio means every $1 invested delivers $3 in social value, such as reduced burnout or increased lifetime earnings.

- The Reality Check: Rigorously adjust for Deadweight (what would have happened anyway) and Attribution (changes caused by other factors) to ensure the foundation only takes credit for the impact it directly catalyzed.

Step 7: Planning for a Responsible Exit

Lastly, a responsible exit preserves the gains made during the funding cycle and strengthens the ecosystem for the long term.

- Transparent Communication: Inform partners early and often about impending exits, ideally starting the conversation at the beginning of the funding relationship.

- Phasing Over: Transfer ownership and responsibility for project activities to local stakeholders, community trust funds, or host-country governments to ensure the work continues after the foundation withdraws.

Conclusion

The pitfalls of DEI measurement are not accidental. Rather, they stem from treating complex human and systemic realities as simple data points. However, when measurement is approached with intention, nuance, and rigor, it becomes a powerful foundation for equitable strategy, accountable practice, and transformative impact.

For foundations and grantmakers, the goal isn’t merely to count diversity, but to measure inclusion and equity in meaningful ways; ways that illuminate power dynamics, remove barriers, and guide equitable resource allocation. When done well, DEI measurement fuels learning, strengthens trust, aligns strategy with values, and ultimately redefines success through an equity lens.